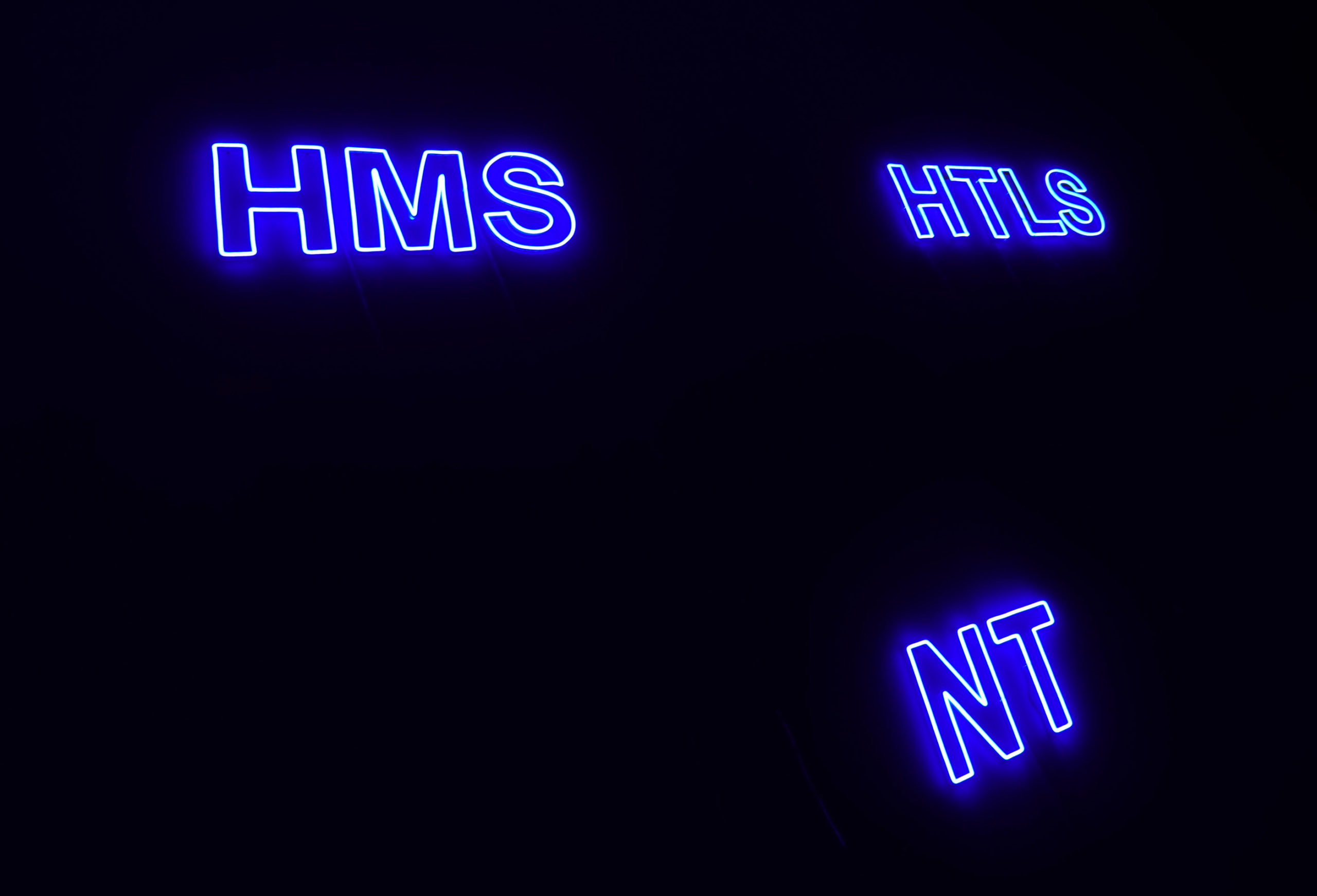

Within the darkened Gallery, ‘HMS NT HTLS’ HOMES NOT HOTELS sizzles in bright neon. The triangle-bound phrase quotes a sign from a recent protest in Blissville, a “forgotten neighbourhood” within Long Island City in which long term residents opposed the erection of a third homeless hotel branded as short-term shelter. New York City is an ongoing case study in gentrification, as wealth and property coalesce against shifting racial, ethnic and cultural boundaries. For long term city residents, Long Island City is a particularly rich cipher, as a rapidly changing and at times conflicted region in which old and new abut. Blissville raises questions around the constant flux of vulnerable people around the city, touching on ongoing community resistance to gentrification and its opposite. It echoes recent protests over homeless people being settled in the Upper West Side due to COVID-19, except that in contrast Queens is known for its multiculturalism and proud pockets of residential architectural preservation. Blissville is a small triangle of mostly industrial buildings with a smattering of residential housing. It sits across the river from heavily gentrified Greenpoint and is a short walk from the gallery. The area was formally established by Neziah Bliss in the nineteenth century as “a utopian laborers community” and for a time it functioned well. As economic demands changed, however, Blissville became a repository for industry alongside one of America’s most polluted waterways. The area is still zoned industrial, so that the existing community can stay but no more can be housed except the dead and the unhoused. The issue of homelessness resembles that in other parts of New York City, however in Blissville the homeless population has at times superseded that of the permanent residents. In recent years a large influx of the unhoused were brought in, housed temporarily in former hotels, which prompted the 2018 unrest.

Kamari Carter and Julian Day, 2020

Carter and Day have built independent practices sculpting and modulating promiscuous natural materials such as sound, air and light in service of their conceptually-driven political practices.

Kamari Carter (he/him) is a producer, performer, sound designer, and installation artist primarily working with sound and found objects. Carter’s practice circumvents materiality and familiarity through a variety of recording and amplification techniques to investigate notions of space, identity, oppression, control, and surveillance. Driven by the probative nature of perception and the concept of conversation and social science, he seeks to expand narrative structures through sonic stillness. Carter has exhibited at MoMA, Fridman Gallery, Automata Arts, Lenfest Center for the Arts, and Issue Project Room. Carter holds a BFA from California Institute of the Arts and an MFA from Columbia University.

https://kamaricarter.portfoliobox.net/

Julian Day (they/them, born Bendigo, Australia) frames sound as a social and civic practice that reveals hidden power dynamics by stealth. This plays out in individual artworks (performance, sculpture, installation, video, text) and projects such as Super Critical Mass in which temporary communities articulate public spaces with interdependent actions. Day has presented work in the California Pacific Triennial, Asia Pacific Triennial, Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Bang On A Can Marathon, MATA, Spitalfields Music Festival, Jewish Museum, Whitechapel Gallery, Fridman Gallery, Institute of Modern Art, Artspace and Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.

EDGE OF LIGHT

EDGE OF LIGHT Virtual Opening & Viewing

Virtual Opening & Viewing